“The Two Charlottes”: Royalty, Britishness and Print Culture

(Given at the Difficult Women in the Long Eighteenth Century: 1680-1830 Conference, Centre of Eighteenth Century Studies, University of York, 27th-28th November 2015)

“… the whole of feminine history has been man-made… the woman problem has always been a man’s problem… [Men have] created values, mores, religions; never have women disputed this empire with them.”[1]

Simone Beauvoir’s now famous argument that all of women’s history had been “man-made” is one that is an important argument to remember within the context of difficult women within the eighteenth century. In particular, affluent and elite women near the end of the long eighteenth century were the intellectual playthings of satirists and pamphlet writers who could make or break a woman’s reputation and social standing. The lack of censorship laws concerning visual prints and the wide range of society who could consume satire and prints is therefore not to be under-estimated. The infamous example of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, succinctly demonstrates how feminine difficulty arose in the minds of contemporary men and how they used satire in order to document the supposed unnaturalness of active women within the political sphere. Not only did men create British society’s values, mores and religions but they also created the images and representations of gender which women were bound by, and visual representations within satire and print were an enduring way to create and maintain approved mores of gender.

At the end of the eighteenth century and after the tempestuous events of the French Revolution, visual representations of upper class British women swiftly became a battlefield. Considering how Britain saw itself as the last bastion of democracy and constitutionalism against the savagery of the French Revolution, as demonstrated in James Gillray’s romantic piece on the bloody execution of King Louis XVI[2], it is therefore interesting to note how aristocratic women within the Regency were portrayed as either caricatured harpies who lived off the blood, sweat and tears of others, were terrible mothers and unfaithful wives; or were represented as English roses whose beauty represented feminine virtue and worth within an increasingly luxuriant aristocratic world at odds with a British constitution. These contentions surrounding accepted aristocratic femininity are perfectly encapsulated in the visual representations of Princess Charlotte and Queen Charlotte within Regency print culture.

The images of Princess Charlotte within this era repeatedly highlight her royal, feminine and domestic identity which seem to be without blemish. This image was understandable given Charlotte’s circumstances. Born on 7th January 1796, nine months almost to the day after her parent’s ill-fated wedding, Charlotte was the only legitimate grandchild of George III and the popular daughter of the ever-popular Princess Caroline. Charlotte was, as an infant, visually associated with her family and the domestic sphere, where her place as a legitimate member of the royal family and as the neglected daughter of the Prince Regent are emphasised; as is seen in Grandpapa in his Glory!! where George III is seen feeding Charlotte who is perched upon his knee in a tableaux of imaginary royal domesticity.[3] In another visual piece around this time Future Prospects, Charlotte is depicted in a scene of domestic disintegration where her father is shown upturning a table whilst Princess Caroline clutches her infant daughter and looking on in utter dismay.[4] Whilst the scene looks more appropriate for a modern day soap opera, the placing of Charlotte in these two prints demonstrates how visual artists and even satirists were visualising Charlotte as an object of public adoration and pity, whilst highlighting her future political position.

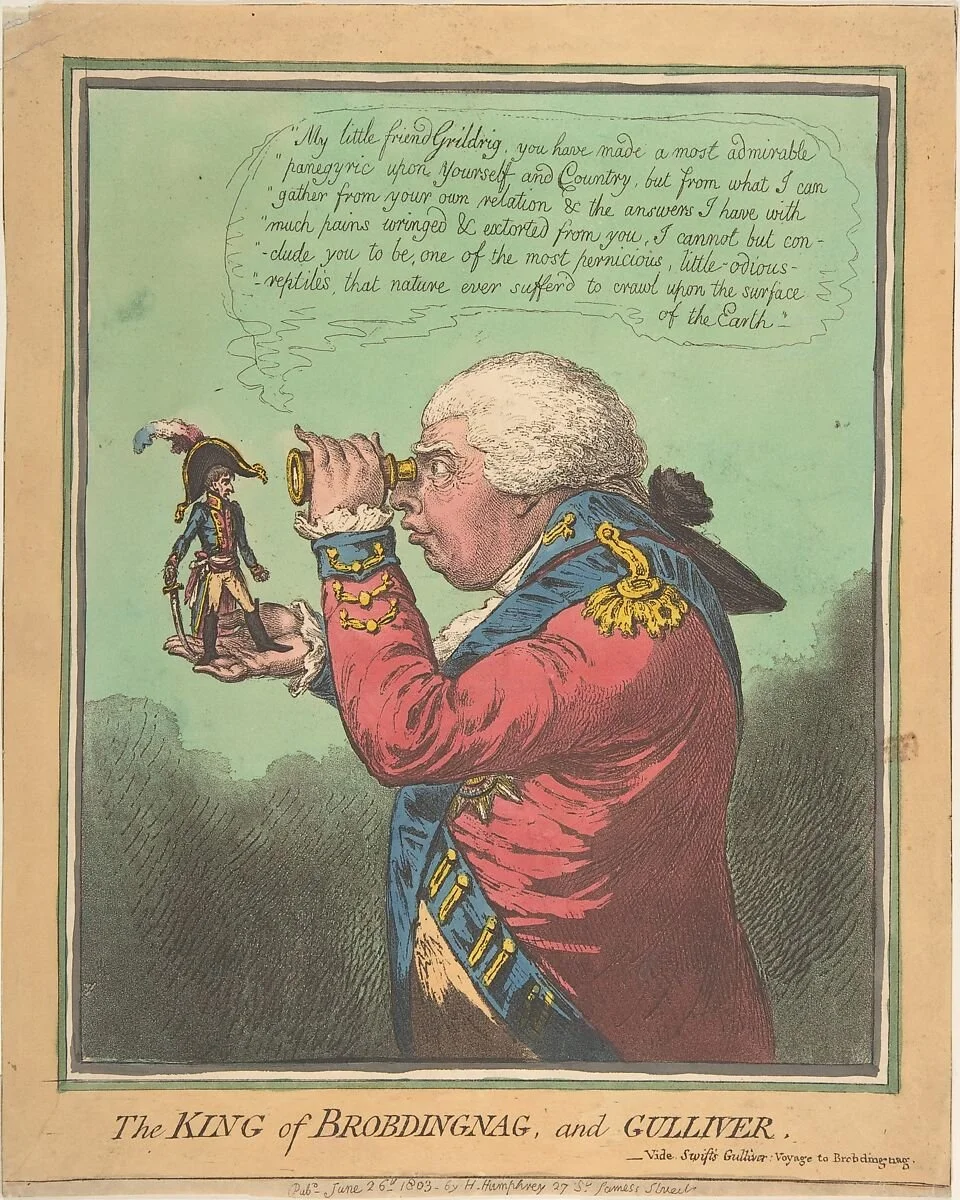

As a future Queen of Britain, the very fact that Charlotte was conceived of as wholly British (in spite of her biological parentage) was established early on in Charlotte’s life, such as in The Little Princess and Gulliver, where a toddler Charlotte is childishly gleeful in dunking a miniature Napoleon in a bowl of water. Not only is Charlotte being placed as a representative of Britain who is actively defeating Napoleon, but this print is also part of the visual tradition concerning George III who styled himself as wholly British and was also previously depicted as a giant compared to the miniscule figure of Napoleon.[5] In this way, we can see how Charlotte, in the mind of visual print artists, was not only continuing the ideal of British dominance against France but was also the natural heir to her popular and proudly British grandfather.

This ideal of continuing the proud, British tradition of George III is the main theme of depictions of Charlotte within the Regency, such as in A Slit In the Breeches, a satirical piece on power within her later marriage to Prince Leopold of Saxe Coburg-Gotha and the later King of the Belgians.[6] Charlotte, whilst depicted as almost comically unladylike in wearing the straining breeches of her emasculated husband, again represents a British identity of bluff self-assurance in Britain’s position in the future, with the accompanying verse declaring in Charlotte’s voice:

“Know sir, with English married pairs,

Whoever here the breeches wears

Remains the master for their life…

Throughout my life, I’ve had my will,

And you shall find I’ll have it still;

Yes, spite of Father, Grandmamma…

[I have] Given [Leopold] a wife, house, food, and riches,

No; curse me, but I’ll wear the breeches.”

Here, Charlotte is attractively defiant against her foreign husband who is near inarticulate in his thick German accent; instead of being a negative portrayal of a wayward royal, Charlotte is again emphasising the proud British feeling that George III had inhabited.

This foundation of Princess Charlotte as a positive visual representation of aristocratic femininity is highlighted again in this period when her marital potential was exploited by satirical artists to fuel popular criticisms of the royal family (which mainly included their assumed uselessness, extravagance and disinterest in their family, both national and personal); with Charlotte being constantly portrayed an English Rose archetype and is normally the only naturalistic figure in many a satire, providing a foil for the pictorial negative of the rest of the royal family and foreigners, as highlighted in scenes which highlighted her beauty and innocence in constructed scenes between a stereotypically German Prince Leopold normally depicted wielding a rather euphemistic sausage.[7]

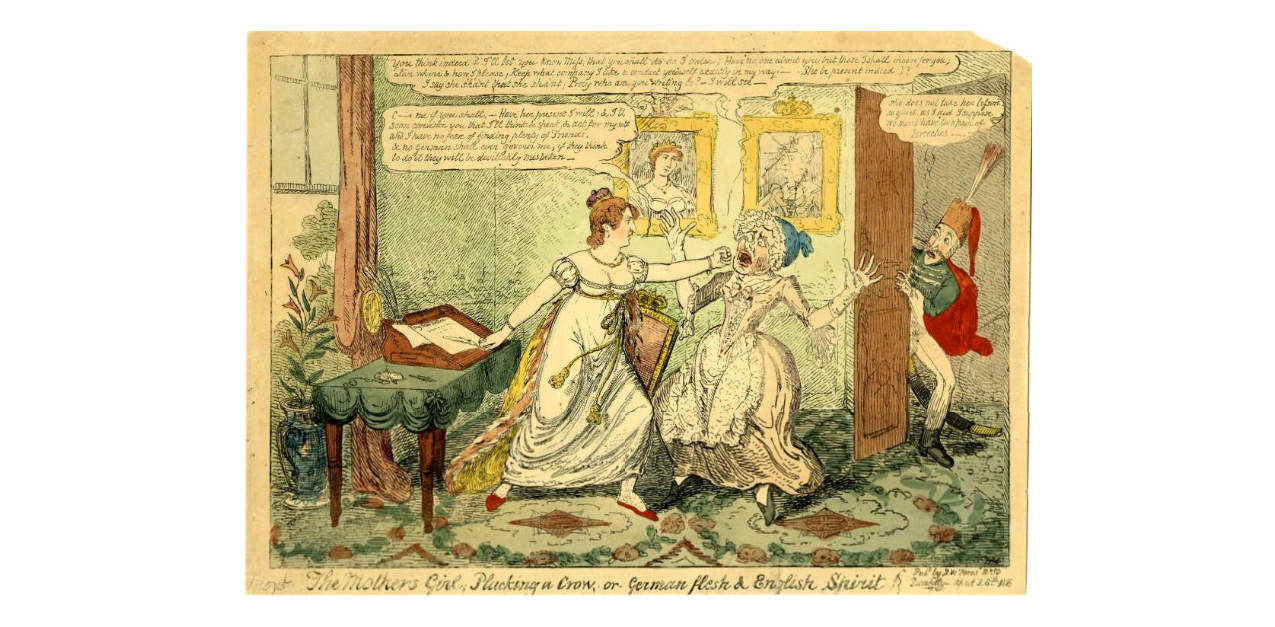

Within these visual representations, Queen Charlotte was constantly portrayed as the very antithesis of her beautiful granddaughter. In depictions of the wider royal family, Princess Charlotte is normally seen in many satire pieces concerning her marriage negotiations, first to the Prince of Orange and later to Prince Leopold, as the beautiful coerced pawn of her greedy family.[8] The rest of the royal family are characterised as the un-British visual trope, particularly the figure of Queen Charlotte whose haggish presence became the staple of Regency satire and the antithesis of her popular granddaughter.[9] In one case, The Mother’s Girl, the Queen is even physically pitched against her granddaughter with Princess Charlotte taking a defiant fist to the ugly, withered face of the unpopular foreign Queen.[10] Whilst nowhere near as bad as previous depictions of the Queen, against the figure of her granddaughter the Queen is evidently the pictorial negative that any satire needed to pitch the figure of pictorial good against. Here is the some direct allusion to the battle of feminine representations and the placing of feminine difficulty to suit an audience.

There are many possible reasons for this visual representation. Queen Charlotte was linked in this period to the increasingly unpopular Prince Regent (who had turned to Toryism and way from the Whiggish leanings of his youth) and therefore was seen as an enemy of the popular Princesses Caroline and Charlotte. Her lack of conventional good looks and foreignness may also have added to British antipathy at a time of increasingly prevalent Britishness (especially during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars), whilst the convention of outward beauty denoting inner beauty or worth was still prevalent in contemporary visual culture (and arguably still resonates today). I would also like to contend that the actual body of Queen Charlotte was also integral to these representations, whose withered breasts and skeletal figure and face are contrasted to the curvaceous and young body of her granddaughter.[11] Whilst female hysteria and ‘uterine disorder’ theories were still to be fully exploited in the later decades of the nineteenth century, contemporary doctors generally believed that “women owe their manner of being to their organs of generation, and especially to the uterus”.[12] As the mother of fifteen children, of whom all were seen either as sexually veracious, useless princes or nunnish, imprisoned princesses, her inability to follow through on the domestic promise of the royal family may have fed into the popular image of a fecund woman who was not a successful mother, both of her children and, by extension, the nation. This is the man-made construction of Princess Charlotte, by comparison, who had no opportunity to be either a successful or an unsuccessful mother, and therefore was able to remain a representation of British hope and constitutional future, which an elderly Queen Charlotte could no longer possibly embody.

However, the perfect visual archetype that Princess Charlotte embodied was completely at odds with reality, as Princess Charlotte was at times a very difficult woman and which demonstrate a reversal of the normal demonization of supposedly difficult women of this period. Her manners were not becoming for a future Queen of Britain, with Lady Charlotte Bury describing how she had “the manners of a hoyden school girl; she talked all sorts of nonsense [and] can put on dignity when she chooses, though it seems to sit uneasily upon her.”[13] She ran away to her mother’s house when plans were made for her to live at Cranbourne Lodge and to see no one but Queen Charlotte in 1813, which led to a public upsurge of pity for her.[14] She was known to overspend, much like her father, with Civil List Expenditures noting a French clock she bought at £735 also in 1813. She was involved in a romantic entanglement with Lieutenant Charles Hesse of the Light Dragoons (reputedly an illegitimate child of the Duke of York) which included forbidden clandestine meetings that might have proven disastrous if publicly revealed. She exacerbated her romantic links to the Duke of Gloucester, which included telling one of the Prince Regent’s agents how she would prefer Gloucester to a foreign match whilst never seriously contemplating Gloucester as a future husband:

“[Doctor Halford] evidently had been desired to sound me about my opinion with respect to marriage, & hint how much more desirable it would be that it should be settled before any establishment took place, wh. would afterwards require to be changed. He spoke very decidedly in favour of the P. of Orange, both as being the wish of the King & he believed the wish of the P[rince] also; saying that there were very few choices to be made that would at once please the family & satisfy the nation, all of wh. seemed to be combined in the person of the P.of O.; as the Queen’s nephew… would never do, as she was so unpopular… [I reminded him that Gloucester was] an Englishman, & that nothing would appear worse in my eyes than a future Queen of England marrying a foreigner, wh., he said was obviated by the young Prince having been educated here.”[15]

In reality, Princess Charlotte was a difficult candidate for the increasingly constitutional throne. Although Parliament had gained more political power through the eighteenth century, the monarch retained a range of constitutional powers. A monarch still held some political power, through the forming of governments, the passing of legislation and the personal support of political parties. The reality of Princess Charlotte may have been a constitutional problem, due to her lack of training for the role, her behaviour around others and her inappropriate romantic trysts. Princess Charlotte was hardly a feminist icon of the late eighteenth century as she was never politically active and never officially aligned herself with either the Prince Regent or Princess Caroline, so her actions shouldn’t be seen as attempts to break away from the patriarchal or constitutional system. At best these actions can be seen as the reactions of a child who has been used as a plaything by her parents and who wants to rebel in a similar way to how Hanoverian heirs tended to rebel against their parents. In this way, we start to understand that the very real difficulties that Princess Charlotte presented were airbrushed away by the medium of popular visual culture, instead of enhanced by satirists to make a satirical point. Her youth, her sex and the hopeful future of a Britain under her constitutional rule were evidently too strong an opiate for contemporaries to resist.

The visual of modern royal Britishness which Princess Charlotte was what print consumers wanted to see, whilst the reminder of the old eighteenth century and the many so called ‘useless hangers on’ of which Queen Charlotte may have been blamed for had become something to be despised and ridiculed. The fantasy of a pseudo-Jane Austen heroine (as Charlotte did see herself as the romantic Marianne or Sense and Sensibility) who represented a young, promising image of Britishness and constitutional government and who was battling the grips of an oppressive family, encapsulated by Queen Charlotte, grabbed the cultural attention of a nation, despite the very real difficulties that Princess Charlotte posed as a future constitutional leader, which can be seen most clearly in the event of Princess Charlotte’s sudden death.

Princess Charlotte’s death was certainly a shock to her family and the nation at large, with this previously robust and healthy woman suffering a fatal haemorrhage after a 48 hour labour on 6th November 1817. In an age where women dying in childbirth or of later complications was a mere one in five[16] (probably due in part to the use of medical equipment such as forceps and the medicalisation of childbirth), Princess Charlotte’s death was the ultimate national tragedy. The future of the British royal family had been snuffed out and what followed was the sudden and brutal disruption of both the immediate and national family.[17]

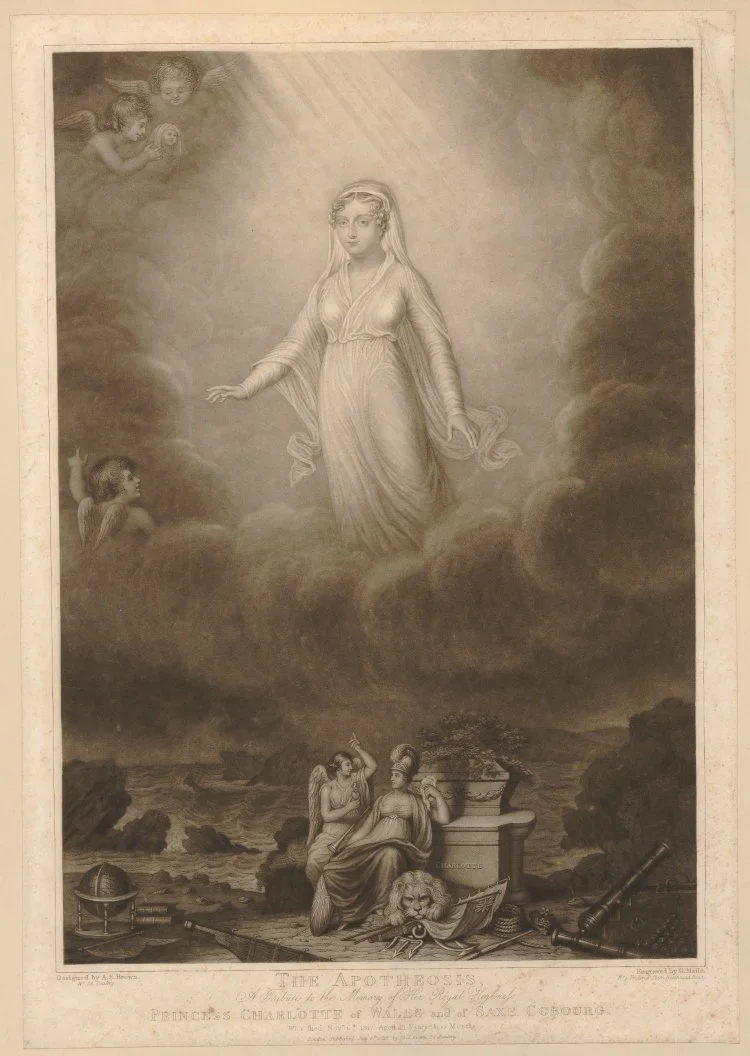

What followed in the year following Princess Charlotte’s death was a cultural movement which attempted to eradicate any question of mortal difficulties concerning Charlotte’s character, which led to a public outcry of grief arguably not seen again until the aftermath of Princess Diana’s death. The main aspects of this grief culture mainly focused upon the destruction of the domestic family, the dashed British future, and the immortalised, amenable person of the deceased princess. Although hardly feminist, this coverage of her life presented to an unknowing populace is a constructed biography portraying Charlotte as a moral being and role model, at stark contrast with her sexually debauched and ageing relatives.

The reactions of other aspects of contemporary print culture which included newspaper reactions exhibit how this blow was seen as a personal bereavement to the public and the royal family, whilst simultaneously the calamitous death of the only legitimate heir to the throne was never denied.[18] The European Magazine wrote how: “[T]he whole people of a mighty Empire, united in one sacred bond of sorrow, mingle their tears with the tears of the Husband and Father…”[19] There is no mention of royal duty or monarchical dynastic loss, instead the language is characterised by domesticity and personal loss of an entire Empire. The Salisbury and Winchester Journal repeated a local address to the Prince Regent, which detailed how the public “have the strongest sense of the public loss thus to convey to your Royal Highness the most lively assurances of our deep sorrow for your paternal sufferings” [20]; whilst The London Gazette also relayed an address from Dumfries to the Prince Regent on the death of his “most amiable, virtuous and illustrious Daughter”.[21] Other forms of print media helped to emphasise the representation of a saint-like Princess Charlotte such as printed sermons, with the British Library alone holding 131 of sermons dedicated to mourning Princess Charlotte’s death and reiterating her roles as daughter, wife, benefactress and good Christian, such as William Naylor’s sermon:

“As a Daughter, she was affectionate to her parents… As a Wife, she was an example to her sex in every rank of society… far from the din of public life, she enjoyed the full cup of domestic felicity… she was liberal to institutions of merit and utility… to vital godliness she was not a stranger.”[22]

There is most probably no way that these writers or the general public could have known Charlotte so personally as to make or corroborate these lofty claims, so we can see how Charlotte is continually seen as more than an heir to the throne or even a real woman, difficult or not, but as a saintly part of a family that the public was invested in.[23]

If we follow Linda Colley’s argument that the idealisation of English female figures took the place of the Roman Catholic Virgin Mary within this era, Charlotte went on to personify this pinnacle of virtuous motherhood in visual culture.[24] In both Ghost as seen in the Hamlet of St Stephens Chapel and Richard Coeur de Diable!!, Charlotte is portrayed clad in white robes, wearing a crown and holding her child close to her breast, a visual reference to visual representations of the Virgin Mary whilst playing heavily on motherhood and blameless spirituality.[25] Her words to her caricatured parents highlight an emphasis on female modesty and virtue for her mother (“Oh such a deed, to live in the rank sweat of an ensemen’d bed stived in corruption”) and a political warning for her father (“Will not the Spirit of thy Relatives once loved through coming from the grave indulge the K-g to banish from his counsels treacherous foes?”). Charlotte is also above reproach or the caricaturist’s reach, trying to save the honour of her mother and the monarchy from mockery and mishap.

Repeatedly in this print culture, no mention is given to her dalliances with men and the Prince of Orange affair is explained away as a political manoeuvre orchestrated by the Prince Regent, which the Austen-like heroine Charlotte could not allow to go ahead due to her lack of romantic feeling towards the Prince of Orange.[26] Charlotte was perceived as a perfect example of womanhood that possessed so much promise for the British Monarchy, compared to popular opinions of the Prince Regent. It was more of the promise of Charlotte being able to help her subjects on a larger scale after her accession that endeared her to her subjects and set her up as a figure of saintly proportions, erasing her potential of being remembered as a difficult woman.

The death of Queen Charlotte in 1818 in comparison failed to capture the public imagination, although her death did not elicit any allusions to her unpopularity. The Lady’s Magazine described the late queen as apolitical, solely interested in her domestic concerns (who even breastfed all her children), and was “the most princely woman in Europe.”[27] Despite this rhetoric for a woman who, in the later years of her life, was met with booing or silence from hostile crowds, it was not the rhetoric of national grief that was experienced across print culture the previous year. Death may have served as a veil that legitimised the imagined difficulties she represented to the British public, but Queen Charlotte was remembered as a “princely woman”, not a daughter or mother of the nation-wide British family. In fact, Princess Charlotte continued to dominate the minds of writers, for at the end of Queen Charlotte’s obituary The Lady’s Magazine states how: “A life-size statue of the Princess Charlotte is now executing [sic] by command of Prince Leopold, previous to his leaving England.” Even in her own obituary, Queen Charlotte’s granddaughter was the one who remained a figure of veneration and continued to demand public attention.

Princess Charlotte as a difficult woman may have been conveniently forgotten by the majority of contemporaries to fulfil a deeper cultural need within British society, but the her more complicated character was not altogether forgotten. Percy Shelley’s An Address to the People on the Death of the Princess Charlotte is one example in a sea of saintly representations where the virtues of Princess Charlotte are not so much rejected but are put in a context where privilege and cultural constructions were laid bare:

“If beauty, youth, innocence, amiable manners, and the exercise of the domestic virtues could alone justify public sorrow when they are extinguished for ever, this interesting Lady would well deserve that exhibition. She was the last and the best of her race. But there were thousands of others equally distinguished as she, for private excellencies [sic], who have been cut off in youth and hope. The accident of her birth neither made her life more virtuous nor her death more worthy of grief. For the public she had done nothing, either good or evil; her education had rendered her incapable of either in a large and comprehensive sense. She was born a Princess; and those who are destined to rule mankind are dispensed with acquiring that wisdom and that experience which is necessary even to rule themselves. She was not like Lady Jane Grey, or Queen Elizabeth, a woman of profound and various learning. She had accomplished nothing, and aspired to nothing, and could understand nothing respecting those great political questions which involve the happiness of those over whom she was destined to rule. Yet this should not be said in blame, but in compassion: let us speak no evil of the dead. Such is the misery, such the impotence of royalty.—Princes are prevented from the cradle from becoming any thing which may deserve that greatest of all rewards next to a good conscience, public admiration and regret.”[28]

Shelley’s Address is one of the few pieces of contemporary literature of its kind, but is something to keep in mind when analysing the figures of royalty and difficult women past and present. It is a piece that understands the man made nature of contemporary public opinion and history, which had erased the very essence of the real and difficult figure of Princess Charlotte in order to establish a cultural consciousness of a lost future of British greatness, only supposedly found again under the rule of Victoria. In our modern age female royal figures, such as Kate Middleton and Diana Spenser, are also represented as perfect role models of femininity despite the more difficult realities of their situations and characters. The airbrushing of the difficulties of feminine reality (or gender reality for that matter) is a cultural phenomenon we are still experiencing and is something that both Queen and Princess Charlotte (and maybe even the brand new Princess Charlotte) would recognise; whilst Shelley’s reasoning also highlights how ‘difficult women’, who may have “private excellencies” and problems shared with the two ‘difficult’ Charlottes of this paper, may have been more common than at first glance.

***

[1] Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (Vintage Classics: London, 1997), 159

[2] James Gillray, The blood of the murdered crying for vengeance (British Museum, London, 1793).

[3] Isaac Cruickshank, Grandpappa in his glory!!! (British Museum, London, 1796).

[4] Anon, Future Prospects (British Museum, London, 1796).

[5] Charles Williams, The Little Princess and Gulliver (British Museum, London, 1803); James Gillray, The King of Brobdingnag (British Museum, London, 1803).

[6] George Cruickshank, A Slit in the Breeches (British Museum, London, 1816).

[7] Charles Williams, Miss out of her teens (British Museum, London, 1816); J. Sidebotham (pub.), Buying A German Sausage (British Museum, London, 1818); Charles Williams, A German Present (British Museum, London, 1816).

[8] One such example includes George Cruickshank, A Novice Entering the convent of St George (British Museum, London, 1814).

[9] James Gillray, Monstrous Caws (British Museum, London, 1787); James Gillray, John Bull and his family leaving off sugar (British Museum, London, 1792).

[10] George Cruickshank, The Mother’s Girl Prucking a Crow (British Museum, London, 1816).

[11] For one earlier example of Queen Charlotte’s physicality, see James Gillray, Sin, death, and the devil. vide Milton (British Museum, London, 1792).

[12] Claude Martin Gardien, Traite complet d’accouchements, et des maladies des filles, des femmes et des enfants, 2nd ed. (Paris, 1816), 1.2-3.

[13] Lady Charlotte Susan Maria Campbell Bury, Diary Illustrative of the Times of George the Fourth Interspersed with Original Letters from… Queen Caroline (Volume 1) (London: H. Colburn, 1838), 13-4 (13th December 1810).

[14] Plowden, pp. 156–160

[15] Letters of Princess Charlotte, 15 October 1813

[16] R. Schofield, ‘Did the Mothers Really Die?: Three centuries of maternal mortality in ‘the world we have lost’’, in The world we have gained: histories of population and social structure, ed. Lloyd Bonfield, Richard M. Smith, and Keith Wrightson (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986), 258, table 9.7; Irvine Loudon, Death in Childbirth: An International Study of Maternal Care and Maternal Mortality, 1800-1950 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992), 165.

[17] Ibid, 164

[18] The European Magazine, November 1817, 383.

[19] The European Magazine, November 1817, 389.

[20] The Salisbury and Winchester Journal December 6, 1817.

[21] The London Gazette December 13, 1817.

[22] William Naylor, A Sermon preached at the Methodist Chapel, Newstreet, York, on the sudden lamented death of Her Royal Highness the Princess Charlotte Augusta (York: Spence and Burdekin, 1817), 25-6.

[23] For examples of poetry, please see: Richard Nottingham, The Tears of Albion, An Ode (London: G. Herbert, c. 1817-18); Charles Phillips, The Lament of the Emerald Isle (London: William Hone, 1817); F. Francis, The Rose of England Nipped in the Bloom (London: D. Cox, 1817).

[24] Linda Colley, Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707-1837 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003), 272.

[25] Anon, Ghost as seen in the Hamlet of St Stephen’s Chapel (British Museum, London, 1820); Anon, Richard Coeur de Diable!!!, (British Museum, London, 1820).

[26] Ibid, 100-101.

[27] The Lady’s Magazine, 1st December 1818.

[28] Italics are my own editing. Percy Bysshe Shelley, An Address to the People on The Death of the Princess Charlotte, Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1817 (http://terpconnect.umd.edu/~djb/shelley/charlotte1880.html, last accessed 26th January 2016).